Section: New Results

Collaboration

Participants : Cédric Fleury [correspondant] , Ignacio Avellino Martinez, Michel Beaudouin-Lafon, Marianela Ciolfi Felice, Carla Griggio, Germán Leiva, Can Liu, Wendy Mackay, Nolwenn Maudet, Joanna Mcgrenere, Midas Nouwens, Yujiro Okuya.

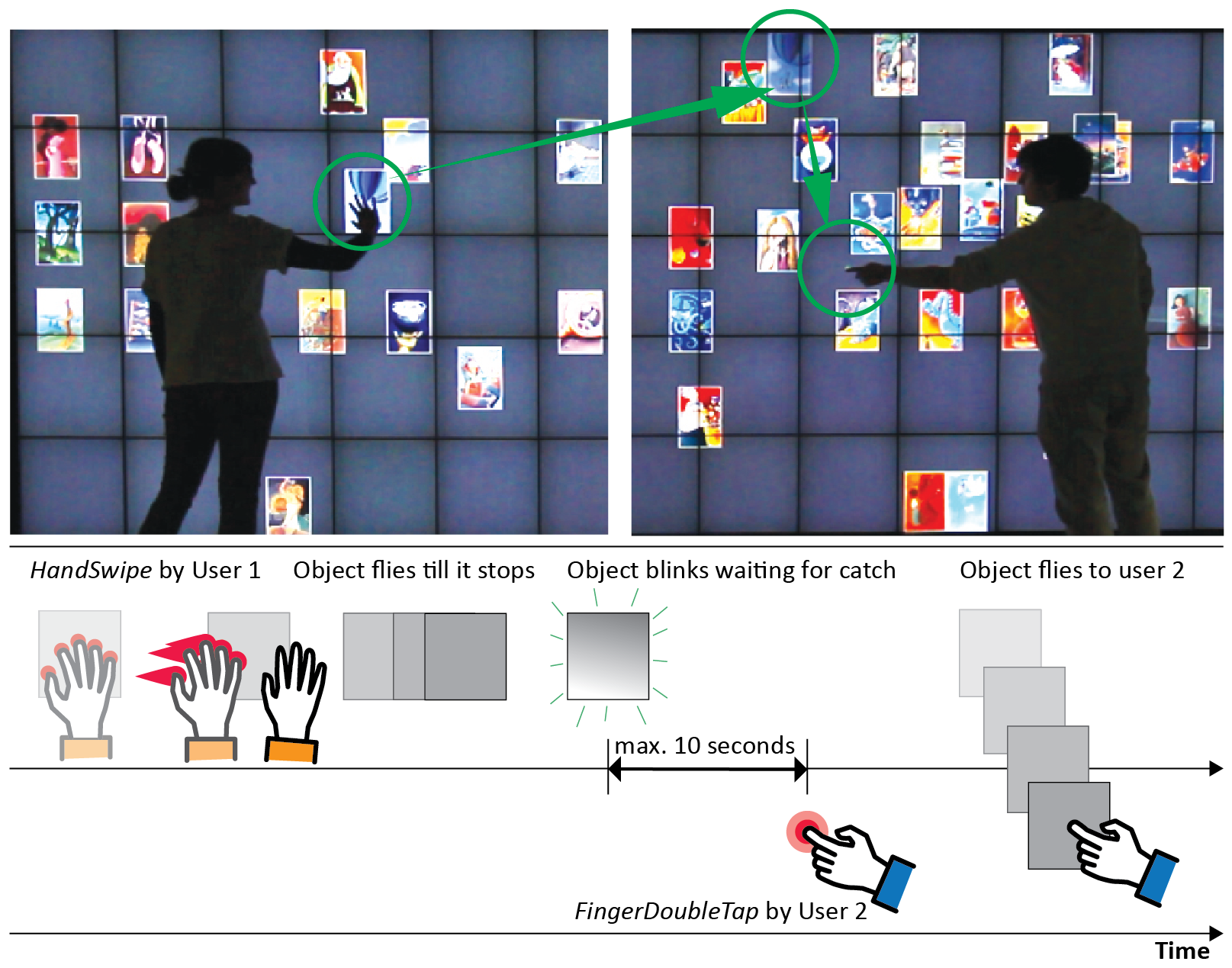

ExSitu is interested in exploring new ways of supporting collaborative interaction, especially within and across large interactive spaces such as those of the Digiscope network (http://digiscope.fr/). Multi-touch wall-sized displays afford collaborative exploration of large datasets and re-organization of digital content. However, standard touch interactions, such as dragging to move content, do not scale well to large surfaces and were not designed to support collaboration, such as passing objects around. We created CoReach [19], a set of collaborative gestures that combine input from multiple users in order to manipulate content, facilitate data exchange and support communication. Throw-and-catch (Figure 5) lets users send digital objects to each other, Preview lets one user show content to another, and SharedClipboard lets users gather content. We conducted an observational study to inform the design of CoReach, and a controlled study showing that it reduced physical fatigue and facilitated collaboration when compared with traditional multi-touch gestures. A final study assessed the value of also allowing input through a handheld tablet to manipulate content from a distance.

We also studied remote collaboration across wall-sized displays, where the challenge is to support audio-video communication among users as they move in front of the display. We created CamRay [15], a platform that uses camera arrays embedded in wall-sized displays (Figure 6) to capture video of users and present it on remote displays according to the users' positions. We investigated two settings: in Follow-Remote, the position of the video window follows the position of the remote user; in Follow-Local, the video window always appears in front of the local user. A controlled experiment showed that with Follow-Remote, participants were faster, used more deictic instructions, interpreted them more accurately, and used fewer words. However, some participants preferred the virtual face-to-face created by Follow-Local when checking for their partners' understanding. An ideal system should therefore combine both modes, in a way that does not hinder the collaborative process. Ignacio Avellino, under the supervision of Michel Beaudouin-Lafon and Cédric Fleury, successfully defended his thesis Supporting Collaborative Practices Across Wall-Sized Displays with Video-Mediated Communication [39] on this topic.

|

We are also interested in the collaboration between between professional interaction designers and software developers when they create novel interactive systems [24]. Although designers and developers have different skills and training, they need to collaborate closely to create interactive systems. Our studies highlighted the mismatches among their processes, tools and representations: We found that current practices create unnecessary rework and cause discrepancies between the original design and the implementation. We identified three types of design breakdowns: omitting critical details, ignoring edge cases, and disregarding technical limitations. In a follow-up study, we found that early involvement of the developer helped mitigate potential design breakdowns but new ones emerged as the project unfolded. Finally, we ran a participatory design session and found that the designer/developer pairs had difficulty representing and communicating pre-existing interactions. This work will inform our future work on tools for designers and developers of interactive systems, in the context of our overal theoretical framework.

We also studied the use of social networks, with an indepth study of how users communicate via multiple apps that offer almost identical functionality [26] We studied how and why users distribute their contacts within their app ecosystem. We found that the contacts in an app affect a user’s conversations with other contacts, their communication patterns in the app, and the quality of their social relationships. Users appropriate the features and technical constraints of their apps to create idiosyncratic communication places, each with its own re- cursively defined membership rules, perceived purposes, and emotional connotations. Users also shift the boundaries of their communication places to accommodate changes in their contacts’ behaviour, the dynamics of their relationships, and the restrictions of the technology. We argue that communi- cation apps should support creating multiple communication places within the same app, relocating conversations across apps, and accessing functionality from other apps.